I think you'd be hard pressed to find some one on the planet who hasn't heard of Lyme disease. In some communities you might have a hard time finding some one who hasn't been bitten by a tick. The dangers of Lyme, and ticks is known. I was recently bitten by a Deer tick, and aware of the damage done by Lyme, I embarked on a quest to be treated. Unfortunately, getting treated properly wasn't easy. Fortunately I have somewhat educated myself to what is really going on in the battle against Lyme. I'm no expert, but I have learned enough to know that all isn't what it seems, and that anyone who lives in an area affected by Lyme, or spending time in the outdoors needs to educate themselves.

Have you ever heard on the Infectious Disease Society of America? Didn't think so. Don't worry, neither had I. The IDSA is a group that studies infectious diseases, and recommends policy, and protocol. Here is their mission Statement, or at least a statement from their "about" page that sure sounds like a mission statement. http://www.idsociety.org/About_IDSA/ sounds good, doesn't it?

As it turns out the IDSA failed to live up to the statement and was found to have a significant amount of conflict of interest among their members assembled to study Lyme.

http://www.ct.gov/ag/cwp/view.asp?a=2795&q=414284 This has led to a policy, and protocols that don't really address the issue, and doctors conflicted on how to treat patients. Fortunately there are doctors out there who are conducting their own research, and writing recommended protocols. Hopefully these studies, and recommendations will have an effect on their peers before more people suffer needlessly. http://www.lymenet.org/BurrGuide200810.pdf

For a little comparison take a look at this link. http://www.lymepa.org/War_On_Lyme_Patients11-08WEB_B_W.pdf

I will state again, I am no expert on Lyme disease. I do have a few recommendations on what you should do in the event you get bitten by a Deer tick.

*First off, go to see a doctor. Many don't know jack about Lyme, but it's still better than blowing it off. It doesn't hurt to get it documented in your medical records that you were bitten by a tick, either.

*Insist on getting a 28 day supply of an antibiotic. It's been shown that rapidly treating Lyme is the best course of action, and that Lyme is harder to cure the longer it goes undetected.

*Save the tick, and send it to a lab to be tested. You want to do this yourself for a couple of reasons. Many hospitals don't test the tick for Lyme, rather they just confirm the tick is in fact a Deer tick. Also, they may not test for any co-infections. Ticks carry more than just Lyme. In the event the tick comes back negative for Lyme, you only need to worry about any co-infection, which may have been handled by the antibiotic you should have already started.

*If your doctor refuses to treat your bite seriously go to another.

A tick bite is natures way of sticking you with a dirty needle. Take it seriously, and get it treated.

The online magazine dedicated to hunting, fishing, and cooking. In the field, on the water, and in the kitchen " all seasons".

Thursday, December 22, 2011

Friday, December 16, 2011

Images Of Success; Deer Hunting

The deer season has been open, in one form or another, across the country (and in others) for some time. I have yet to tip one over, but I have recieved some photos of the success others have had. I thought I'd share, so here they are.

Tommy with an 8 pointer.

Mich (in Japan) with his first deer.

Bruce (on the right) with the Nantucket wind chimes.

Mike with a fine NC buck. Mike was featured with his spring bear earlier this year.

Santa scored this year, too.

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

Streamside With GW; Calling It Like It Is.

I thought I knew this river. Like so many things in life, be they women, wine, authors, or friends, I knew one side of it, and was surprised when I saw something unexpected in front of me later. I have fished it before, upstream a bit where the fishery is heavily managed to the point where pieces of railroad tie divert it and give cover to the fish. Until recently I considered this river a theme park for trout fisherman, and I have grappled with the identity of the river as a place where old fisherman come to catch fish they have names for and a place where inexperienced people can come to fly-fish, perchance casting their lines across each other. I have plenty of opportunities to punch rude people in Boston, so I have avoided it since the first time I fished there in a pair of rubber clamming waders.

I soothed the urgency of winter early one spring with a white-knuckle trip during a warming trend that I thought for sure would bring off a hatch. The pretty day I planned on turned out to be not-so-pretty and climaxed with a light flurry… all but a short stretch of the same river was frozen bank-to-bank except for where I stopped, threw my gear on, and fished anyway. While I was standing in a river that by all rights should have been skated upon, with dudes whizzing by 100 yards behind me on snow-mobiles, and making fists around my rod-guides to melt away the ice, I caught the finest brown trout of my life that day after ignoring no less than a half-dozen good reasons to bag on the entire trip. Tell your boys not to pass on a girl who isn’t so pretty in high school, she may just turn into a gem later.

In between the upper part of the river and the lower stretch where I caught that beautiful brown, there is a meandering slither where the water goes by icy and smooth as if it were a melted flow of pure diamond so clear that the wavering clumps of vegetation (green, darker green, and brown) could be waving calmly off the backs of the stones in five feet of water or one. Behind the cobbles and in the feeding lanes, the trout are feeding, resting, or pestering each other. They can see you, and will often post up right behind you and pick food out the plume your wading makes… Don’t hunt these fish, they’re fucking with you. Drift something audacious instead through the feeding lanes where the less opportunistic trout have fought to make their bread and butter. A patch of cobble and waving weeds will change into a flash of light and you can tighten your line well.

You will catch rainbow trout whose heartiness and beauty will break your heart if you can outsmart them; these are educated fish, for the love of all things holy don’t hurt them; throw some stiff wood, bring them up, and thrash them across the surface, into your net, and release them wiser so that they may grow longer, stronger, and fertile. There are some pretty epic browns lurking in the calmer water too, countless wee brookies combing the riffles, and some landlocks that wash over the dam to break your ass off when you are trying to fish light. I am like you; I call bullshit on people who claim to catch 24-inch salmon in a Massachusetts river…. meet in the middle and fish a 5-weight.

And remember; respect the river. We may be watching.

**Contributed by ASO Pro-Staffer George W. George is Boston area artist, real estate professional, and an outspoken trout fanatic.

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Dogging It.

It's been a dog training weekend. Sure, I could have snuck off to a treestand, duck blind, or grouse covert, but sometimes ya just gotta slow down. Plus, I've got a busy week planned, where I'll be sneaking off to a treestand, a duck blind, and a grouse covert. Just not in that that order. So I worked with Ginger on some basics, with some tricky cover thrown in. I want her to succeed as a duck dog, too, so I've been keeping her in wet, thick, and tricky cover.

In this first video, I don't do anything tricky. I toss a marked retrieve, and send her for it at my leisure. Ginger has been struggling with her steadiness a bit; she doesn't run in, but creeps, and doesn't stay seated. So she doesn't get to make the retrieve until her butt hits the ground.

Here, I toss a dummy into tricky, wet cover. Ginger still creeps, so I give her a little reminder, and put a bit of pressure on her. Of course, she makes the retrieve, and makes it look easy, too.

In this last video I toss the dummy into heavy, thick, wet cover. The water depth in this cover varies, and the cover is tall, so not only is Ginger doing more swimming, but we can't see each other much. If you're planning to use your spaniel for waterfowling you've got to have a spaniel that can handle this type of cover and get the job done. You need a dog that is brave, trustworthy, and independent.

**Special thanks to my wife for the wonderful, professional looking video job.

In this first video, I don't do anything tricky. I toss a marked retrieve, and send her for it at my leisure. Ginger has been struggling with her steadiness a bit; she doesn't run in, but creeps, and doesn't stay seated. So she doesn't get to make the retrieve until her butt hits the ground.

Here, I toss a dummy into tricky, wet cover. Ginger still creeps, so I give her a little reminder, and put a bit of pressure on her. Of course, she makes the retrieve, and makes it look easy, too.

In this last video I toss the dummy into heavy, thick, wet cover. The water depth in this cover varies, and the cover is tall, so not only is Ginger doing more swimming, but we can't see each other much. If you're planning to use your spaniel for waterfowling you've got to have a spaniel that can handle this type of cover and get the job done. You need a dog that is brave, trustworthy, and independent.

**Special thanks to my wife for the wonderful, professional looking video job.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Waterfowl-Water Foul. Adventures In The Muck.

Waterfowling is a passion of many a sportsman around the globe. My friend Tim is one of those sportsmen, so whenever an invite is floated my way I am sure to accept. Today Tim, along with his Chessie Pogue, and I trekked in the predawn blackness to the brush choked, muddy shore of a beaver impoundment Tim frequents. The effort was well worth it.

To assure we'd have ample time to bushwhack in and set decoys, I rolled out of bed at 4 AM, and turned the car north 15 minutes later. By 5:30 Tim and I were dressed and making our way in, and had our set up completed about 20 minutes later. This actually allowed us 15+ minutes of listening to mallards quacking, wings whistling, and duck butts splashing down. One minute after shooting time arrived I found myself swinging on a trio of ducks set to land in our spread. The butt to shoulder-cheek to stock- muzzle to bird-finger to trigger scenario played out in perfect syncronization, and the duck disappeared. The splash and concentric rings in the water confirmed what we knew, and Pogue was sent for the first retrieve of the day. Not being a regular fowler, I am usually happy when any fowl makes it home with me, and even a single duck is considered a "success". In turn, my focus has been on increasing my species list. I've shot Mallards, Blacks, Woodie, Pintails, and now I could add Gadwall to the list. For the next 15 minutes we announced our position to the world with an almost steady volley of shots. I'd like to tell you that by the time it slowed down we'd sent the dog to pick a number of well shot birds, but I can't.

As the action slowed, ducks still came in, worked the decoys, and held our attention. Some shots were still offered, and some spectacular misses were recorded by us both. Such is the art of wing shooting. To our right Mallards teased us, setting into an inpenetratable mess, while to our left Teal zoomed in, landing in open water too far away. Eventually it was time to pick up the decoys, and prepare to go to work, so we resigned ourselves to the fact that we need more time at skeet.

As Tim waded out to the first decoy he insisted that I remain by the shore, loaded, and looking. He assured me that as Murphy prescribed so many years ago, that ducks will come in while the decoys are being pulled. He was right, and I soon knocked a drake Mallard into the weeds about 50 yards to our left. To our surprise Pogue started back without the drake. No big deal. We'd finish picking up, walk the shore close to the mark, and send him again on a hunt dead. Of course I made this harder to do by splashing down a passing Canada goose. The goose wasn't dead on the water, and required Pogue to give considerable chase. When the goose crossed a section of the beaver dam Pogue got the leverage he needed, leaping from atop the dam directly onto the goose. A job well done, by the somewhat aging veteran.

Picking the Mallard proved to be more of a chore than we expected, too. We both expected the drake to be dead, but put it out from under a blow where it had been hiding. Again, Pogue gave chase while the duck made a series of submarine maneuvers to avoid capture. At one point, while well clear of the dog, Tim even shot it again, but it kept swimming. Soon the drake dove, and never resurfaced. Pogue was directed to the area where he searched and searched. We'd considered waiting out the duck, but time wasn't on our side, and painfully the decision was made to abandon the search with the hope that Tim and Pogue could make it back there before sunset to try a hunt dead search again.

While lost game, and a friend shooting zeros isn't anyone's idea of a good time, and I take no joy in them, the morning was exceptional. The only thing that held us back was ourselves, and had we been shooting better, no doubt we'd have been damned close to carrying out a limit. We are both excited to team up for a duck hunt again soon, and now that I've seen the beaver impoundment, and what it holds for cover, I'll bring Ginger to get her share of the work.

To assure we'd have ample time to bushwhack in and set decoys, I rolled out of bed at 4 AM, and turned the car north 15 minutes later. By 5:30 Tim and I were dressed and making our way in, and had our set up completed about 20 minutes later. This actually allowed us 15+ minutes of listening to mallards quacking, wings whistling, and duck butts splashing down. One minute after shooting time arrived I found myself swinging on a trio of ducks set to land in our spread. The butt to shoulder-cheek to stock- muzzle to bird-finger to trigger scenario played out in perfect syncronization, and the duck disappeared. The splash and concentric rings in the water confirmed what we knew, and Pogue was sent for the first retrieve of the day. Not being a regular fowler, I am usually happy when any fowl makes it home with me, and even a single duck is considered a "success". In turn, my focus has been on increasing my species list. I've shot Mallards, Blacks, Woodie, Pintails, and now I could add Gadwall to the list. For the next 15 minutes we announced our position to the world with an almost steady volley of shots. I'd like to tell you that by the time it slowed down we'd sent the dog to pick a number of well shot birds, but I can't.

As the action slowed, ducks still came in, worked the decoys, and held our attention. Some shots were still offered, and some spectacular misses were recorded by us both. Such is the art of wing shooting. To our right Mallards teased us, setting into an inpenetratable mess, while to our left Teal zoomed in, landing in open water too far away. Eventually it was time to pick up the decoys, and prepare to go to work, so we resigned ourselves to the fact that we need more time at skeet.

As Tim waded out to the first decoy he insisted that I remain by the shore, loaded, and looking. He assured me that as Murphy prescribed so many years ago, that ducks will come in while the decoys are being pulled. He was right, and I soon knocked a drake Mallard into the weeds about 50 yards to our left. To our surprise Pogue started back without the drake. No big deal. We'd finish picking up, walk the shore close to the mark, and send him again on a hunt dead. Of course I made this harder to do by splashing down a passing Canada goose. The goose wasn't dead on the water, and required Pogue to give considerable chase. When the goose crossed a section of the beaver dam Pogue got the leverage he needed, leaping from atop the dam directly onto the goose. A job well done, by the somewhat aging veteran.

Picking the Mallard proved to be more of a chore than we expected, too. We both expected the drake to be dead, but put it out from under a blow where it had been hiding. Again, Pogue gave chase while the duck made a series of submarine maneuvers to avoid capture. At one point, while well clear of the dog, Tim even shot it again, but it kept swimming. Soon the drake dove, and never resurfaced. Pogue was directed to the area where he searched and searched. We'd considered waiting out the duck, but time wasn't on our side, and painfully the decision was made to abandon the search with the hope that Tim and Pogue could make it back there before sunset to try a hunt dead search again.

While lost game, and a friend shooting zeros isn't anyone's idea of a good time, and I take no joy in them, the morning was exceptional. The only thing that held us back was ourselves, and had we been shooting better, no doubt we'd have been damned close to carrying out a limit. We are both excited to team up for a duck hunt again soon, and now that I've seen the beaver impoundment, and what it holds for cover, I'll bring Ginger to get her share of the work.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

From The Ground Up; Thoughts On Foot Care

All things being equal, I often consider the feet to be a hunters number one asset. One day afield with I'll fitting boots, or an errant step while crossing a blow down are usually what it takes to get us thinking about our feet. Sometimes sitting in camp with our throbbing feet up, scotch and Advil coursing our veins is what makes us take notice and motivates us to buy new boots. A look at what our feet do for us reveals their importance. Our feet take us to our tree stands, and carry us up. Our feet allow us to follow bird dogs through coverts, and kick out tight holding birds. Our feet allow us sure footing while wading rivers and fighting big trout. Here are a few of my thoughts, and a few things I do to keep my feet happy, and ultimately insure I spend more time afield.

Foot Wear- we all know the importance of proper foot wear, but I'll say it again. The right foot wear will make your adventures more pleasurable. It's never when we're wearing the right boot that we think about it, so it's hard to fully appreciate your choice. The fit of the boot is important; make sure they fit correctly. If your heel floats in the back, you're bound for blisterville.

Quality socks make a difference, too. Depending on the weather, I prefer a wool sock, but a cushion foot boot sock in the warmer months gets the trick done.

They type of boot you use can make a difference. Deer hunters have seen a swing from traditionally styled hunting boots to rubber boots, though either kind will do the job provided the boot is matched to your hunting style. Same goes for bird hunters. Those hunting in dry conditions will benefit from a light weight moc-toe boot. That said, I use rubber boots for both deer, and bird hunting. I value the water tightness of a pair of rubber wellies, and traditional New England grouse cover is usually wet. Wellies can be found in a number of configuration; insulated/ un-insulated, camo, or plain, ankle fit, or not.

After the hunt- there are things you can do, post hunt, to help your feet recover for the next hunt. Obviously, a warm soaking feels good, but cold will benefit you more. One trick I use it to take a standard therapeutic sports wrap, and freeze it. In the evening I sit with the wrap under my arches for 10-15 minutes. The cold pushes the fluids, which collect in your feet out. After removing your feet from the cold wrap you will quickly feel the rush of fresh blood flowing back into your feet.

In extreme circumstances such as a twisted ankle, or a sore Achilles tendon, you can immerse your feet in an ice bath. A small dish washing tub filled with some ice and cold water will do the trick. Remember to keep the ice bath to 10-15 minutes, as any longer can cause cold burns.

Foot Wear- we all know the importance of proper foot wear, but I'll say it again. The right foot wear will make your adventures more pleasurable. It's never when we're wearing the right boot that we think about it, so it's hard to fully appreciate your choice. The fit of the boot is important; make sure they fit correctly. If your heel floats in the back, you're bound for blisterville.

Quality socks make a difference, too. Depending on the weather, I prefer a wool sock, but a cushion foot boot sock in the warmer months gets the trick done.

They type of boot you use can make a difference. Deer hunters have seen a swing from traditionally styled hunting boots to rubber boots, though either kind will do the job provided the boot is matched to your hunting style. Same goes for bird hunters. Those hunting in dry conditions will benefit from a light weight moc-toe boot. That said, I use rubber boots for both deer, and bird hunting. I value the water tightness of a pair of rubber wellies, and traditional New England grouse cover is usually wet. Wellies can be found in a number of configuration; insulated/ un-insulated, camo, or plain, ankle fit, or not.

After the hunt- there are things you can do, post hunt, to help your feet recover for the next hunt. Obviously, a warm soaking feels good, but cold will benefit you more. One trick I use it to take a standard therapeutic sports wrap, and freeze it. In the evening I sit with the wrap under my arches for 10-15 minutes. The cold pushes the fluids, which collect in your feet out. After removing your feet from the cold wrap you will quickly feel the rush of fresh blood flowing back into your feet.

In extreme circumstances such as a twisted ankle, or a sore Achilles tendon, you can immerse your feet in an ice bath. A small dish washing tub filled with some ice and cold water will do the trick. Remember to keep the ice bath to 10-15 minutes, as any longer can cause cold burns.

If you really feel like treating yourself, book some reflexology. A good foot massage can do wonders. Many shopping malls have massage and reflexology shops. With the holiday season approaching it is a sure bet that your spouse will drag you around shopping. This may present you with the perfect opportunity to sneak a reflexology session in.

Sunday, November 13, 2011

Kiji Tatsuta

As thrilling as the hunt is, the time spent in the kitchen preparing and serving a hard won meal can be equally exciting, and satisfying as a heavy game bag. The extent that sportsmen go to, in their efforts to be able to smooth the breast feathers, and feel the heft of a bird delivered to hand by a trusted dog, it's no wonder so many spend as much time perfecting their culinary skills, as their clay scores. Of course, knowing your way around the kitchen also brings with it a certain awe in camp, and almost always assures one will be exempt from doing dishes after the meal.

With the responsibility of taking game comes the responsibility of creating a masterpiece with it. While it seems these skills improve with age, and bird camp experience, there is always someone who draws the line at doing little more than opening a canned cream of mushroom soup and a bag of onion bits. Coupled with the need for a forgotten appetizer, a culinary whiz in camp is always more than welcomed.

Of course we all want our game birds to be picturesque center pieces, but let's not forget they make great apps, and snacks too. As a frequent traveler to Japan, and a lover of Asian food, I've found a series of treatments not only suitable for game birds, but pleasing to the American palate too. One of the foods I've adapted is a fried chicken recipe, suitable for either a main dish or an appetizer, called Tatsuta Age (Tah-Tsu-Tah Ah-Gay), but this recipe will work with any white breasted game bird. In Japanese, Pheasant is called Kiji (Kee Jee), so I call this dish, Kiji Tatsuta.

Tastuta is a dish in which bite sized pieces of chicken are marinated in some basic ingredients, and deep fried to deliciousness. The simplicity of this dish, coupled with the familiarity of deep frying make this dish an easy primer for anyone interested in expanding the flavor profiles of their cooking, and is sure to impress the guys; whether served at hunting camp, or while watching a football game. In addition, two of the ingredients are a staple I use in treating any bird I take that might be hard hit and suffering a little rankness from blood trapped in the meat.

To start you'll need to take a trip down the international aisle at the grocery store for a couple of provisions, and then detour to the produce section, before venturing into the kitchen. To start with, find yourself a bottle of soy sauce, and a small bottle of cooking sake. Cooking sake is a very low alcohol content rice wine, and should be available at any large grocery store. Should you not find it, any inexpensive bottle of sake from the liquor store will do. I like to keep a large bottle on hand, as it comes in handy for other game handling applications, which I'll explain later. From the produce aisle you'll need some scallions, and a roughly one inch long piece of ginger root. In addition you'll need to get some oil for frying and some flour, if you don't have it already.

Taking a look at our ingredients, here's what you should have assembled when it's time to start cooking:

The breast meat of two pheasant. Cut into bite sized chunks

Soy sauce

Cooking sake, or regular sake

Ginger root, roughly one inch in size

Scallions

Flour

Oil

Assembling this dish is quite easy. Put two parts sake, and one part soy sauce in a bowl suitable for marinating. About 2/3 cup of sake, and 1/3 cup of soy sauce should be enough. Finely chop two scallions, and add to the soy/sake mixture. Next, grate the ginger, retaining any liquid, and add about one tablespoon to the mixture. Ginger can be grated with a small, fine cheese grater, or chopped finely if you have the knife skills. Before grating, you can quickly remove the paper-like skin of the ginger by scraping it off with the edge of a spoon, or you can include it in the dish. After you've assembled, and mixed your marinade, submerse the meat and refrigerate for a couple of hours. When it's time to cook, simply pull a couple chunks of meat from the marinade, allowing bits of scallion and ginger to adhered to it, dredge it in flour, and carefully drop it in the hot oil you've heated until it's fried golden brown.

This combo of ingredients will give the meat a warming, refreshing accent, which will keep everyone’s fingers traveling from the serving plate to their mouths. The simplicity of this recipe allow for easy modification. More ginger or scallion can be added to suit ones taste, and should you want to make this as a meal, just cut your meat to a larger size and fry a bit longer. The first time you make it, you may want to only use half of the ginger, increasing to your taste as you go.

This is an article I thought was going to be publish, and maybe it will yet. After several issues of the publication going out without it, however, I thought it was time to share it.

With the responsibility of taking game comes the responsibility of creating a masterpiece with it. While it seems these skills improve with age, and bird camp experience, there is always someone who draws the line at doing little more than opening a canned cream of mushroom soup and a bag of onion bits. Coupled with the need for a forgotten appetizer, a culinary whiz in camp is always more than welcomed.

Of course we all want our game birds to be picturesque center pieces, but let's not forget they make great apps, and snacks too. As a frequent traveler to Japan, and a lover of Asian food, I've found a series of treatments not only suitable for game birds, but pleasing to the American palate too. One of the foods I've adapted is a fried chicken recipe, suitable for either a main dish or an appetizer, called Tatsuta Age (Tah-Tsu-Tah Ah-Gay), but this recipe will work with any white breasted game bird. In Japanese, Pheasant is called Kiji (Kee Jee), so I call this dish, Kiji Tatsuta.

Tastuta is a dish in which bite sized pieces of chicken are marinated in some basic ingredients, and deep fried to deliciousness. The simplicity of this dish, coupled with the familiarity of deep frying make this dish an easy primer for anyone interested in expanding the flavor profiles of their cooking, and is sure to impress the guys; whether served at hunting camp, or while watching a football game. In addition, two of the ingredients are a staple I use in treating any bird I take that might be hard hit and suffering a little rankness from blood trapped in the meat.

To start you'll need to take a trip down the international aisle at the grocery store for a couple of provisions, and then detour to the produce section, before venturing into the kitchen. To start with, find yourself a bottle of soy sauce, and a small bottle of cooking sake. Cooking sake is a very low alcohol content rice wine, and should be available at any large grocery store. Should you not find it, any inexpensive bottle of sake from the liquor store will do. I like to keep a large bottle on hand, as it comes in handy for other game handling applications, which I'll explain later. From the produce aisle you'll need some scallions, and a roughly one inch long piece of ginger root. In addition you'll need to get some oil for frying and some flour, if you don't have it already.

Taking a look at our ingredients, here's what you should have assembled when it's time to start cooking:

The breast meat of two pheasant. Cut into bite sized chunks

Soy sauce

Cooking sake, or regular sake

Ginger root, roughly one inch in size

Scallions

Flour

Oil

Assembling this dish is quite easy. Put two parts sake, and one part soy sauce in a bowl suitable for marinating. About 2/3 cup of sake, and 1/3 cup of soy sauce should be enough. Finely chop two scallions, and add to the soy/sake mixture. Next, grate the ginger, retaining any liquid, and add about one tablespoon to the mixture. Ginger can be grated with a small, fine cheese grater, or chopped finely if you have the knife skills. Before grating, you can quickly remove the paper-like skin of the ginger by scraping it off with the edge of a spoon, or you can include it in the dish. After you've assembled, and mixed your marinade, submerse the meat and refrigerate for a couple of hours. When it's time to cook, simply pull a couple chunks of meat from the marinade, allowing bits of scallion and ginger to adhered to it, dredge it in flour, and carefully drop it in the hot oil you've heated until it's fried golden brown.

In addition, sake is a great treatment for hard hit birds. On occasion, I find that I may have a bird in my fridge, that either from being hard hit, or suffering from a poor diet, has a bit of a rank odor to it. Simply marinating a bird such as this in sake, and a couple 1/4 inch thick rounds of ginger easily removes any unwanted essence, without impacting the flavor.

Bon appetite.

Bon appetite.

This is an article I thought was going to be publish, and maybe it will yet. After several issues of the publication going out without it, however, I thought it was time to share it.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Grouse Camp 2011 Photos

What is it, really, that brings us all to grouse camp each fall? It must be something truly special to motivate one to pack dog, gear and gun into a cramped car, and turn north to the farthest reaches of New Hampshire. I've got it easy, only driving up from Boston, but others make the trip from more southerly points; New Jersey, New York City, Pennsylvania,.....and in past years, even from as far away as Colorado. Perhaps it's the thrill of sneaking away from civilization, and staying in a rustic camp?

Or the view it provides?

Maybe it's the thrill of getting to hunt and share camp with this guy? But I doubt it.

I think it's about covers filled with potential,.....

and the vistas travelled between them.

But even more, I think it's about good friends, and gun dogs.

Often the surprises we encounter along the way become cherished memories,......*

but mostly, it's the birds that bring us together.

Special thanks to ASO Pro Staffers Bryan, and Sterling for providing the photos.

* If you ever have a chance to meet Sterling, ask him about his cherished memory of a Black Bear surprise in Pennsylvania.

Or the view it provides?

Maybe it's the thrill of getting to hunt and share camp with this guy? But I doubt it.

I think it's about covers filled with potential,.....

But even more, I think it's about good friends, and gun dogs.

Sterling & Tim

Steve & Lula

Myself & Bryan

Lula

Often the surprises we encounter along the way become cherished memories,......*

Woodies flushed from a creek

but mostly, it's the birds that bring us together.

Special thanks to ASO Pro Staffers Bryan, and Sterling for providing the photos.

* If you ever have a chance to meet Sterling, ask him about his cherished memory of a Black Bear surprise in Pennsylvania.

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Things You Should Check Out; Safety & Navigation Recommendations

This installment of Things You Should Check Out covers a few items I use, and recommend for safety and navigation. Naturally navigation goes hand in hand with safety. After all, not getting home at the end of the hunt is fundamentally unsafe.

The Delorme Gazetteer is a great item to add to your gear bag. Deform makes a topo atlas of all 50 states, showing a variety of features you're bound to find useful. My collection of Delorme are worn, chewed by puppies, stained with gun solvent, and well marked with highlighter pen. While too big to be carried afield they can be studied before heading out for an adventure.

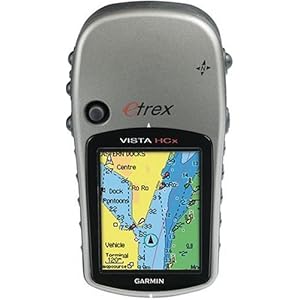

A GPS is another item that will allow one to safely venture into parts unknown, and back again. There are quite a few companies making GPSs, and many different kinds available. I use a Garmin eTrex Vista HCx. This model has downloadable topo maps, so not only can you see where you are, but what lays ahead. Any waypoint, or track you save in the device can be saved on your computer, so maps can be made, or over-layed on Google Earth. The GPS has allowed me to find and hunt cover I would have never been in. The Garmin etrex

The last thing I'll recommend is the shooting glasses being offered by Ducks Unlimited. These glasses come with a case and five different shooting lenses. The set includes two low light lenses in yellow, and orange, a bronze lens for bright days, a blue lens for clay shooting, and a clear lens. In addition to the obvious benefits of glasses when shooting, they also have a navigational benefit. Should you ever find yourself pressed into navigating the woods after dark (not recommended) you can put on the clear lens, and protect yourself from the twig, or branch that will try to poke your eye out. DU Shooting glasses

The Delorme Gazetteer is a great item to add to your gear bag. Deform makes a topo atlas of all 50 states, showing a variety of features you're bound to find useful. My collection of Delorme are worn, chewed by puppies, stained with gun solvent, and well marked with highlighter pen. While too big to be carried afield they can be studied before heading out for an adventure.

A GPS is another item that will allow one to safely venture into parts unknown, and back again. There are quite a few companies making GPSs, and many different kinds available. I use a Garmin eTrex Vista HCx. This model has downloadable topo maps, so not only can you see where you are, but what lays ahead. Any waypoint, or track you save in the device can be saved on your computer, so maps can be made, or over-layed on Google Earth. The GPS has allowed me to find and hunt cover I would have never been in. The Garmin etrex

The last thing I'll recommend is the shooting glasses being offered by Ducks Unlimited. These glasses come with a case and five different shooting lenses. The set includes two low light lenses in yellow, and orange, a bronze lens for bright days, a blue lens for clay shooting, and a clear lens. In addition to the obvious benefits of glasses when shooting, they also have a navigational benefit. Should you ever find yourself pressed into navigating the woods after dark (not recommended) you can put on the clear lens, and protect yourself from the twig, or branch that will try to poke your eye out. DU Shooting glasses

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

A Shooting Sport Rant

Last week while grouse hunting up north I found myself needing to buy a box of shells. No problem, I'll just pop into the local sporting goods store, and grab a box off the shelf. That's exactly what I did. But I was reminded of a conversation I'd had with my friend Sterling a week before while grouse hunting. I paid $17.50 for a box of 20 gauge, high brass 7 1/2s. But price isn't the subject of this rant. The fact that by next season any un-used shell which has been rolled in my pocket, thumbed, and been allowed to commingle with other shells will be indistinguishable from any other shell is my problem. For $17.50 per box, the manufacturers could at least mark their products with ink that doesn't wear off so easily. While I usually dedicate one pocket for 7 1/2s, and another for 6s, by the end of the season shells often end up mixed together some how. When it comes time again to use these shells, I sure would like to know that it's a 7 1/2 I'm dropping in the right barrel, and a 6 I'm dropping it the left barrel. Is that too much to ask? Rant over.

Sunday, November 6, 2011

The Learning Curve; More Grouse Hunting

Another journey north, to the grouse woods of northern New Hampshire served to further expand my knowledge of this most noble bird. What did I learn? That's easy. I learned that grouse hunting without a dog sucks. Sure, grouse can be hunted without, and with some company to help move the birds forward you're sure to sling some lead. But solo, truly solo; no dog, no friends, it's a different, and much more challenging game. And the birds sure seemed to know the difference, preceding to flush behind me after I'd moved past them.

As I'm sure you could guess, my idea of accessorizing is a lanyard with dog whistle around my neck. And if you've been following my blog, you'll know I've got no one to blame for my dog less position but myself. I should have started a pup a couple years ago, and been prepared for the inevitable passing of Austin, my setter. But sometimes we don't make the best decisions, or think clearly, so I must resign myself to less intense grouse season, and a more intense dog training season. Happily, the latter is making up for the former, and Ginger, my springer pup is coming along grand.

All hope was not lost on this last trip north, however. I took some time to venture deeper into an area I'd hunted last year, and the trip proved out my suspicions. I moved quite a few birds in there. Of course this marks a growing understanding of the functions of my GPS. Now that I've had the GPS a couple of years, and experimented with it's functions, I've gotten to the point where I feel comfortable busting brush into parts unknown, and using it to navigate my way back. That was precisely what I did. Last year, in unseasonable heat, Bryan and I hunted this area for a couple of hours. We hunted it in the typical walk the trail while the dog courses the cover routine. The heat, however, sapped the energy of both dog and man, and we quit hunting quite early every day we were there. This year I felt the call of the wild, and went where the cover took me.

The birds in the cover often seemed, to my detriment, to not really care too much about my presence. Sure, they were sneeky, and flushed behind obstructions, but they flew as if they'd never seen a human before. This should have been a recipe for success, should your measure of success be a heavy game bag, but I found myself being punished in other ways. I'd decided I'd carry my 28 gauge Gamba over/under into that covert. That turned out to be a mistake. Not the result of bad shooting, so stop thinking it. But rather a more mundane, and foolish annoyance. Being a rather cold day, I'd elected to wear gloves. I say elected, as if I had a choice, but I didn't. It was about 22 degree in the morning, and had only warmed to about 32 degrees by the time I was in the woods. The Gamba, of course has a rather low profile thumb safety,.....yup. Safety trouble of the highest order. Three softballs go up, and three times I fail to switch the safety off. A dog wouldn't have helped in this case, but at least I'd have had a companion to bitch at. But I can't blame the gun, nor the lack of a dog, nor the weather. I can't blame anything, or anyone for my troubles afield. It is, after all, grouse hunting.

As I'm sure you could guess, my idea of accessorizing is a lanyard with dog whistle around my neck. And if you've been following my blog, you'll know I've got no one to blame for my dog less position but myself. I should have started a pup a couple years ago, and been prepared for the inevitable passing of Austin, my setter. But sometimes we don't make the best decisions, or think clearly, so I must resign myself to less intense grouse season, and a more intense dog training season. Happily, the latter is making up for the former, and Ginger, my springer pup is coming along grand.

All hope was not lost on this last trip north, however. I took some time to venture deeper into an area I'd hunted last year, and the trip proved out my suspicions. I moved quite a few birds in there. Of course this marks a growing understanding of the functions of my GPS. Now that I've had the GPS a couple of years, and experimented with it's functions, I've gotten to the point where I feel comfortable busting brush into parts unknown, and using it to navigate my way back. That was precisely what I did. Last year, in unseasonable heat, Bryan and I hunted this area for a couple of hours. We hunted it in the typical walk the trail while the dog courses the cover routine. The heat, however, sapped the energy of both dog and man, and we quit hunting quite early every day we were there. This year I felt the call of the wild, and went where the cover took me.

The birds in the cover often seemed, to my detriment, to not really care too much about my presence. Sure, they were sneeky, and flushed behind obstructions, but they flew as if they'd never seen a human before. This should have been a recipe for success, should your measure of success be a heavy game bag, but I found myself being punished in other ways. I'd decided I'd carry my 28 gauge Gamba over/under into that covert. That turned out to be a mistake. Not the result of bad shooting, so stop thinking it. But rather a more mundane, and foolish annoyance. Being a rather cold day, I'd elected to wear gloves. I say elected, as if I had a choice, but I didn't. It was about 22 degree in the morning, and had only warmed to about 32 degrees by the time I was in the woods. The Gamba, of course has a rather low profile thumb safety,.....yup. Safety trouble of the highest order. Three softballs go up, and three times I fail to switch the safety off. A dog wouldn't have helped in this case, but at least I'd have had a companion to bitch at. But I can't blame the gun, nor the lack of a dog, nor the weather. I can't blame anything, or anyone for my troubles afield. It is, after all, grouse hunting.

Sunday, October 30, 2011

A Partnership For Success

The autumn woods, alive with kaleidoscopic colors, and the moist earthy smells of composting leaves, religiously draw sportsmen, and their dogs to impenetrable tangles of thorn, and boot swallowing bramble in search of grouse and woodcock every year. Many of them, like myself, are prone to temporary bouts of amnesia, forgetting birthdays, names, and the where-a-bouts of the honey do list, as the humidity of summer passes, and the temperature slowly falls. It's a time of the year when a gundogs place in the family pecking order quickly rises, while shotguns of every imaginable configuration are cleaned, inspected, and cleaned again. Familiar grouse coverts, and tote roads worn with boot traffic bring a sense of relief like no easy chair and tumbler has ever provided during the off season. While the pleasure of watching ones dog course the woods in search of grouse scent is held in higher esteem than a first class upgrade, and the intensity of a bird well pointed holds more excitement than a Stanley Cup over-time game, the end result sometimes fizzles, rather than pops, because no extra hours on the sporting clays course, nor weekends working with dog trainers can take the survival instinct out of the grouse.

Pointing dogs, being the choice of most grouse hunters, can reveal the location of quite a few grouse in their life time, but making the most of the situation requires more than just a heads up dog, and a keen shooting eye. The Ruffed Grouse's compulsion to run requires dog and handler to form a partnership to put birds before the gun. Countless water-colors depict the lone hunter and his staunch dog, locked onto a grouse flushing straight away from the base of a tree in a long abandoned orchard, but it seldom happens this way. The idea of strolling behind your dog, and sauntering up to his point for a shot may work on plantations lousy with quail, but in the grouse woods, especially when hunting solo, it's better to be proactive. Not only will a little forward thinking put more birds in your bag, but it'll greatly improve the bond between man and dog. Here are a few tips that will help you and your dog to enjoy more grouse hunting success, no matter how you define it.

Trust your dogs nose- For the most part, the upland hunter uses a dog because it's olfactory system has the ability to detect and decipher the tasty smells of nature. As the scent moves from the dogs nose to it's brain, the dog communicates to us it's excitement through subtle changes in body movement. How we react to that movement can either break or seal a deal. While a dog should hunt for the handler, rather than going where, and doing what it pleases, it should be given some latitude. A dog that lifts it's head, and looks in a direction other than that being traveled might be telling you something, and encouraged to investigate. The same with a dog who, while running a beat, circles back and double checks an area behind you. Grouse are cunning, and will circle around on occasion. Though we'd like to think we're pressuring a bird, and moving it ahead, that's not always the case. A dog that checks it's back trail could well end up pointing a bird behind you.

Resist stopping the dog- The Whoa command is a great command. It ensures steadiness in a young dog, can re-enforce manners when running multiple dogs, and can be a great safety tool when near roadways. Used too often, it can give a running grouse a head start every time you use it. Once a dog has become grouse wise, and knows not to crowd birds, the whoa command should be used sparingly. Allowing your dog to reposition as the grouse moves on keeps both you, and the dog closer to the bird as it try's to make it's escape. A dog with good grouse sense will expertly handle all the repositioning on it's own, until pinning the bird. To build this grouse sense in your dog you've got trust him. Laying off the whoa command allow this to happen, and strengthens the bond you two share, as well as increase your enjoyment afield together. Refraining from using the command also keeps you from having to walk over and release the dog after it has complied with the command.

Get Ahead- Hand in hand with allowing your dog to reposition, and probably the biggest piece of the partnership puzzle, is knowing when to get ahead of your dog. I'm not talking about moving in on a point, but hustling well ahead and letting the dog work towards you. Once a dog has become birdy, and it is clear it's working the hot scent of a runner, make a big loop forward so as to end up between 30 to 50 yards ahead of him. Then either start working back towards him slowly, or move back and forth perpendicular to his path, as he herds the running grouse forward. Once the bird realizes it's between the two of you it'll find a hide out, and be pointed. This tactic is easy if you hunting along a tote, or a gated road, as you can get on the road and quickly move ahead. A word of caution, however. This tactic is for the solo hunter. When hunting with others safety is paramount; always know where your shooting partners are. It is best, if hunting with a group, to refrain from having someone circle ahead, but rather have two flankers, designated as shooters, move forward quickly, parallel to the track of the dog. This will cause a grouse to either hold until it can be pointed, or come unglued.

Silence is golden- keeping voice communications to a minimum will leave the wary grouse guessing as to your where-a-bouts until it's too late. When your dog is pushing a running grouse, your dog represents the imminent threat to the bird, and it's only thinking about escaping the dog. When you begin pushing in on a point, the threat changes, and you become the imminent threat. The bird is now focused of you. Why alert the grouse to your presents before it's absolutely necessary by giving commands, or encouragement? Letting your presence be a surprise might just be the thing needed to force the grouse to make a mistake in choosing it's escape path, putting right in front of your muzzles.

Know your coverts- Grouse can be predictable. If you are familiar with your cover, you'll have a better understanding of how the grouse move about in that cover. Some smaller covers will allow you to predict with stunning accuracy where, and which direction a grouse will flush. When this happens you can begin to dissect the cover by casting your dog in a direction you know will influence a birds behavior on the ground. By paying attention to the features In coverts you're intimately familiar with, you will begin to see similar feature in new coverts, and can adapt a strategy for you and the dog based experience elsewhere. Speeding up, or slowing down, based on experience elsewhere may well have you and your dog pinning birds quicker and easier.

Double the dog- Not only is it exciting watching two dogs working in tandem, but it's double the scenting power. Should you be lucky enough to have two pointing dogs this maybe something you want to try. Naturally, the dogs should hunt independently, and have different ranges. The wider, bigger running dog has as much chance of pressuring a bird to move towards you, as it comes around on it's beat, as it does away. When it does, the bird will find itself between the two dogs. You'll find this represents a different kind of threat to the grouse, causing them to hold sooner, ground routes cut off.

Next time you're in the woods, just you and the dog, think about these tips, and give one, or all of them a try. I think they'll help you get productive points quicker. Your dog works hard for you, and you should work just as hard for him. After all, your relationship is real a partnership, and the success of the solo wingshooter depends on the success of the dog, so help him out. You're game bag will appreciate it.

**This is a piece I wrote back in June and shopped around to some outdoor publications. While I recieved good feed back from editors who liked the idea, none wanted to spend money on it. Seems budgets are tight in the periodical world right now. Anyway, here it is now for your enjoyment.

Pointing dogs, being the choice of most grouse hunters, can reveal the location of quite a few grouse in their life time, but making the most of the situation requires more than just a heads up dog, and a keen shooting eye. The Ruffed Grouse's compulsion to run requires dog and handler to form a partnership to put birds before the gun. Countless water-colors depict the lone hunter and his staunch dog, locked onto a grouse flushing straight away from the base of a tree in a long abandoned orchard, but it seldom happens this way. The idea of strolling behind your dog, and sauntering up to his point for a shot may work on plantations lousy with quail, but in the grouse woods, especially when hunting solo, it's better to be proactive. Not only will a little forward thinking put more birds in your bag, but it'll greatly improve the bond between man and dog. Here are a few tips that will help you and your dog to enjoy more grouse hunting success, no matter how you define it.

Trust your dogs nose- For the most part, the upland hunter uses a dog because it's olfactory system has the ability to detect and decipher the tasty smells of nature. As the scent moves from the dogs nose to it's brain, the dog communicates to us it's excitement through subtle changes in body movement. How we react to that movement can either break or seal a deal. While a dog should hunt for the handler, rather than going where, and doing what it pleases, it should be given some latitude. A dog that lifts it's head, and looks in a direction other than that being traveled might be telling you something, and encouraged to investigate. The same with a dog who, while running a beat, circles back and double checks an area behind you. Grouse are cunning, and will circle around on occasion. Though we'd like to think we're pressuring a bird, and moving it ahead, that's not always the case. A dog that checks it's back trail could well end up pointing a bird behind you.

Resist stopping the dog- The Whoa command is a great command. It ensures steadiness in a young dog, can re-enforce manners when running multiple dogs, and can be a great safety tool when near roadways. Used too often, it can give a running grouse a head start every time you use it. Once a dog has become grouse wise, and knows not to crowd birds, the whoa command should be used sparingly. Allowing your dog to reposition as the grouse moves on keeps both you, and the dog closer to the bird as it try's to make it's escape. A dog with good grouse sense will expertly handle all the repositioning on it's own, until pinning the bird. To build this grouse sense in your dog you've got trust him. Laying off the whoa command allow this to happen, and strengthens the bond you two share, as well as increase your enjoyment afield together. Refraining from using the command also keeps you from having to walk over and release the dog after it has complied with the command.

Get Ahead- Hand in hand with allowing your dog to reposition, and probably the biggest piece of the partnership puzzle, is knowing when to get ahead of your dog. I'm not talking about moving in on a point, but hustling well ahead and letting the dog work towards you. Once a dog has become birdy, and it is clear it's working the hot scent of a runner, make a big loop forward so as to end up between 30 to 50 yards ahead of him. Then either start working back towards him slowly, or move back and forth perpendicular to his path, as he herds the running grouse forward. Once the bird realizes it's between the two of you it'll find a hide out, and be pointed. This tactic is easy if you hunting along a tote, or a gated road, as you can get on the road and quickly move ahead. A word of caution, however. This tactic is for the solo hunter. When hunting with others safety is paramount; always know where your shooting partners are. It is best, if hunting with a group, to refrain from having someone circle ahead, but rather have two flankers, designated as shooters, move forward quickly, parallel to the track of the dog. This will cause a grouse to either hold until it can be pointed, or come unglued.

Silence is golden- keeping voice communications to a minimum will leave the wary grouse guessing as to your where-a-bouts until it's too late. When your dog is pushing a running grouse, your dog represents the imminent threat to the bird, and it's only thinking about escaping the dog. When you begin pushing in on a point, the threat changes, and you become the imminent threat. The bird is now focused of you. Why alert the grouse to your presents before it's absolutely necessary by giving commands, or encouragement? Letting your presence be a surprise might just be the thing needed to force the grouse to make a mistake in choosing it's escape path, putting right in front of your muzzles.

Know your coverts- Grouse can be predictable. If you are familiar with your cover, you'll have a better understanding of how the grouse move about in that cover. Some smaller covers will allow you to predict with stunning accuracy where, and which direction a grouse will flush. When this happens you can begin to dissect the cover by casting your dog in a direction you know will influence a birds behavior on the ground. By paying attention to the features In coverts you're intimately familiar with, you will begin to see similar feature in new coverts, and can adapt a strategy for you and the dog based experience elsewhere. Speeding up, or slowing down, based on experience elsewhere may well have you and your dog pinning birds quicker and easier.

Double the dog- Not only is it exciting watching two dogs working in tandem, but it's double the scenting power. Should you be lucky enough to have two pointing dogs this maybe something you want to try. Naturally, the dogs should hunt independently, and have different ranges. The wider, bigger running dog has as much chance of pressuring a bird to move towards you, as it comes around on it's beat, as it does away. When it does, the bird will find itself between the two dogs. You'll find this represents a different kind of threat to the grouse, causing them to hold sooner, ground routes cut off.

Next time you're in the woods, just you and the dog, think about these tips, and give one, or all of them a try. I think they'll help you get productive points quicker. Your dog works hard for you, and you should work just as hard for him. After all, your relationship is real a partnership, and the success of the solo wingshooter depends on the success of the dog, so help him out. You're game bag will appreciate it.

**This is a piece I wrote back in June and shopped around to some outdoor publications. While I recieved good feed back from editors who liked the idea, none wanted to spend money on it. Seems budgets are tight in the periodical world right now. Anyway, here it is now for your enjoyment.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Grouse Camp '11

Last Wednesday Ginger and I pointed the car north right about the time the sun was peeking over the horizon. With a steaming cup of coffee, a cooler full of groceries, and an amped up puppy I headed to grouse camp where for five days my good friend Bryan, and I would chase grouse, woodcock, and bunnies. As usual we'd be hunting with the same cast of characters who make the trip to hunt with us. Of course, sometimes we make the trip to hunt with them.

Our grouse camp has been a tradition for about 12 years now, but has changed in form slightly over the years. When we started organizing the camp most of us lived in Massachusetts, so making the trip to Coos county, New Hampshire twice a season was easy. As job transfers, and promotions found a few relocating to NYC and Pa it became time to rethink the location of camp. For a few years we made the trip to Pa, but that wasn't working out too good for everyone. We ended up finding a location in western NY where the bird numbers were good, and the driving time reasonable for everyone.

This year, however, things didn't shape up as we'd wanted them to, so Bryan and I, decided to salvage the season by booking a cabin in Coos county again. Of course invitations were sent out, and soon it was realized that we'd gone from no camp, back to our original camp up north. The differences didn't end there. A couple members could make it due to family and work commitments. There were dog issues, too. Most of the dogs of the earlier camps were either retired, or passed on. This left us with an elderly GSP, Lula, a middle aged Chessie, Pogue, and a young Lab, Ruby. Yes, my Springer Pup, Ginger, made the trip, but she wouldn't hunt; she's not ready yet.

There are a lot of ways to measure success when it comes to hunting, and grouse hunting is no exception. It's also rare that you meet someone at a camp that doesn't wish they'd killed a few more grouse, so it's hard to measure along the birds killed scale. So how is the success measured?

Here's how I see it; The company was exceptional. To be able to share a camp with like minded, ethical sportsman, who have become good friends over the years is hard to beat.

Like always, we all pride ourselves in our abilities in the kitchen. Grilled woodcock, pulled pork, T-bone steaks, and beef stew are just a few of the culinary delights we feasted on. Followed each evening by a dram of scotch, or a glass wine was the cherry atop the Sundae.

Dog work, too, provided some great entertainment. Pogue, unfortunately came up lame early and was left to rest, but Ruby and Lula both put on a show. Lula has a rather metered gate, and isn't very fast, but proved to be methodical. At past camps she had always found herself beaten to the birds. Without faster legs in camp this year she was pointing grouse and woodcock right out of the box. Seeing a weekend pheasant dog perform like this for us was a joy. And Ruby, whose been trained strictly as a duck dog hit her stride in the uplands. Once a species was kicked up, and shot over her, she took in the info needed to track em down, and put em in front of the gun. Yet another grand performance.

The weather held out pretty good, too. We got some rain in the mornings, but by the time we were ready to hit the woods it had usually passed. The Temp held in the high 40's, and low 50's, and the overcast sky kept the sun from blinding anyone as they swung on a bird.

The area of the county we were staying in being known for it's grouse population, mean that the other cabins were almost always occupied by other bird hunters, and the occasional moose hunter. This year was no exception, but in the mornings when everyone let their dogs out, rather than seeing pointers, setters, and GSPs running around the lawn, it was all spaniels. A contingent from the Patriot Sporting Spaniel Club, in New Hampshire happened to be there the same time we were. Incidentally, the Secretary of the club, who I'd been having an e-mail exchange with about membership just the week before, was in the cabin next to our. By the time we left I'd met 7 members of the club, and 15 spaniels.

There is one thing I learned I need to work on for future grouse camps. My video skills are lacking, and I didn't manage the camera as well as I could have. Sorry. Not much video to share with you all. but here are a couple. One is of the All Seasons Outdoor "pro staffers" getting ready to get in the woods. The other is Bryan showing off a nice grouse he scratched down.

The hardest thing about grouse camp is waiting for it to get here. I'm not going to have to wait too long, as I'm headed back up, solo this time, to hit the woods for 4 more days. But then the waiting begins, and as Ginger progresses in her training I'm sure it'll seem like the time until next grouse camp is crawling by. Fortunately I have local grouse and woodcock to chase, as well as ducks, and deer. But it's the grouse that makes the blood course through my veins.

Our grouse camp has been a tradition for about 12 years now, but has changed in form slightly over the years. When we started organizing the camp most of us lived in Massachusetts, so making the trip to Coos county, New Hampshire twice a season was easy. As job transfers, and promotions found a few relocating to NYC and Pa it became time to rethink the location of camp. For a few years we made the trip to Pa, but that wasn't working out too good for everyone. We ended up finding a location in western NY where the bird numbers were good, and the driving time reasonable for everyone.

This year, however, things didn't shape up as we'd wanted them to, so Bryan and I, decided to salvage the season by booking a cabin in Coos county again. Of course invitations were sent out, and soon it was realized that we'd gone from no camp, back to our original camp up north. The differences didn't end there. A couple members could make it due to family and work commitments. There were dog issues, too. Most of the dogs of the earlier camps were either retired, or passed on. This left us with an elderly GSP, Lula, a middle aged Chessie, Pogue, and a young Lab, Ruby. Yes, my Springer Pup, Ginger, made the trip, but she wouldn't hunt; she's not ready yet.

There are a lot of ways to measure success when it comes to hunting, and grouse hunting is no exception. It's also rare that you meet someone at a camp that doesn't wish they'd killed a few more grouse, so it's hard to measure along the birds killed scale. So how is the success measured?

Here's how I see it; The company was exceptional. To be able to share a camp with like minded, ethical sportsman, who have become good friends over the years is hard to beat.

Like always, we all pride ourselves in our abilities in the kitchen. Grilled woodcock, pulled pork, T-bone steaks, and beef stew are just a few of the culinary delights we feasted on. Followed each evening by a dram of scotch, or a glass wine was the cherry atop the Sundae.

Dog work, too, provided some great entertainment. Pogue, unfortunately came up lame early and was left to rest, but Ruby and Lula both put on a show. Lula has a rather metered gate, and isn't very fast, but proved to be methodical. At past camps she had always found herself beaten to the birds. Without faster legs in camp this year she was pointing grouse and woodcock right out of the box. Seeing a weekend pheasant dog perform like this for us was a joy. And Ruby, whose been trained strictly as a duck dog hit her stride in the uplands. Once a species was kicked up, and shot over her, she took in the info needed to track em down, and put em in front of the gun. Yet another grand performance.

The weather held out pretty good, too. We got some rain in the mornings, but by the time we were ready to hit the woods it had usually passed. The Temp held in the high 40's, and low 50's, and the overcast sky kept the sun from blinding anyone as they swung on a bird.

The area of the county we were staying in being known for it's grouse population, mean that the other cabins were almost always occupied by other bird hunters, and the occasional moose hunter. This year was no exception, but in the mornings when everyone let their dogs out, rather than seeing pointers, setters, and GSPs running around the lawn, it was all spaniels. A contingent from the Patriot Sporting Spaniel Club, in New Hampshire happened to be there the same time we were. Incidentally, the Secretary of the club, who I'd been having an e-mail exchange with about membership just the week before, was in the cabin next to our. By the time we left I'd met 7 members of the club, and 15 spaniels.

There is one thing I learned I need to work on for future grouse camps. My video skills are lacking, and I didn't manage the camera as well as I could have. Sorry. Not much video to share with you all. but here are a couple. One is of the All Seasons Outdoor "pro staffers" getting ready to get in the woods. The other is Bryan showing off a nice grouse he scratched down.

The hardest thing about grouse camp is waiting for it to get here. I'm not going to have to wait too long, as I'm headed back up, solo this time, to hit the woods for 4 more days. But then the waiting begins, and as Ginger progresses in her training I'm sure it'll seem like the time until next grouse camp is crawling by. Fortunately I have local grouse and woodcock to chase, as well as ducks, and deer. But it's the grouse that makes the blood course through my veins.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Time To Occupy

I'm sure you've noticed, like I have that an "occupy" movement has been sweeping across the country, and maybe even the globe, now. I guess which ever side of the turmoil coin you look at there is something to be angry about. I haven't really studied the issues, and I probably should, but it has occurred to me that while the occupiers are occupying, and standing up for their cause(s), they might want to study another cause they can add to the list. As I've stated, I haven't studied the issues, so I may be remiss in suggesting it, but the occupiers seem to not have noticed that their comfort in tent city has been much better than expected for October. Yup. The weather has supported their movement. And maybe it should serve as an indicator that they should add climate change to their agenda.

I don't much believe the global warming theory, but I do believe that something is affecting the behavior of our weather systems, and our climate. I'm also pretty certain that we (the humans inhabiting the planet) are responsible for it. I probably contribute my share to the destruction, too, having moved some years ago to an area which requires me to have a car. Whether emission is a factor or not in the climate issue, I drive way more than I should; I drive to work, the grocery store, into town, to the gym, to the kennel, and go hunting and fishing. Some things are unavoidable, and driving to escape the city will remain a neseccary evil.

I have decided, in the spirit of the occupy movement, and their avoidance of the climate change issue to hold my own "occupation". Unfortunately, it comes with a little environmental sacrifice, and a bit of road time, but tomorrow morning I will occupy the drivers seat of my car for about 4 hours, as I head north to newest hot bed of protest; Occupy Grouse Camp.

I don't much believe the global warming theory, but I do believe that something is affecting the behavior of our weather systems, and our climate. I'm also pretty certain that we (the humans inhabiting the planet) are responsible for it. I probably contribute my share to the destruction, too, having moved some years ago to an area which requires me to have a car. Whether emission is a factor or not in the climate issue, I drive way more than I should; I drive to work, the grocery store, into town, to the gym, to the kennel, and go hunting and fishing. Some things are unavoidable, and driving to escape the city will remain a neseccary evil.

I have decided, in the spirit of the occupy movement, and their avoidance of the climate change issue to hold my own "occupation". Unfortunately, it comes with a little environmental sacrifice, and a bit of road time, but tomorrow morning I will occupy the drivers seat of my car for about 4 hours, as I head north to newest hot bed of protest; Occupy Grouse Camp.

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Things You Should Check Out, Youtube Channel

The All Seasons Outdoors Youtube channel is up and running, and I will be posting more outdoor related videos as I get them. You can look forward to seeing dog training, hunting, fishing, and a variety of other interesting videos, which hopefully will be enjoyable and helpful. Many of the videos you will have seen before, as I intend to embed video into related stories. I hope you enjoy it.

http://www.youtube.com/user/Allseasonsoutdoors

http://www.youtube.com/user/Allseasonsoutdoors

Monday, October 10, 2011

Grouse Cover 101

The upland tradition is alive, taking place in various forms all across the country. In the west hunters carry themselves across hostile rocky terrain in search of Chukars, while down south hunters in wagons drawn by mules, follow muscular Pointers across plantations brimming with quail. The Dakotas see military like formations of walkers and blockers push hundreds of pheasant across the sky, and in the woodlands of New England picturesque Setters, and side by side shotguns chase Ruffed Grouse through the autumn colors. For many in New England, however, the uplands consists of wildlife management areas, generously stocked with pheasants. American favorite game bird, once wild to these parts, but now a rarity, has found it's demand much greater than it's supply. The Ruffed Grouse, and the Woodcock, by contrast, are still wild, and in many places abundant. And finding them may not be as hard as you'd imagine.

Surprisingly, I've found that many uplanders don't pursue the ruffed grouse. Not many uplanders don't know what a grouse is, but haven't made the effort to give them a go. The reasons vary, and many may not have an interest, but for those that do, and would like to try, there is only one thing you need to know to make a go of it; What is grouse habitat.

Like all animals in the forest, grouse inhabit a particular habitat. I learned a long time ago, that to be a successful grouse hunter, one doesn't hunt grouse, one hunts grouse habitat (cover). That is; if you try to find grouse buy looking for grouse, you won't find many, but if you try to find grouse by finding where they want to be, they'll be there. But what is grouse habitat? How can I find it? Let's take a look.

The first thing to know is that grouse like early growth successional habitat, often called second growth cover. What is that? Well, it's quite simply young woodland under 25 years old. This type of young forest allows sun light to reach the forest floor, resulting in a carpet of thick vegetation in which the grouse can feed, and move undetected by avian predators. Now, it's not quite as simple as finding this type of cover, but if this was all you were to remember, you'd be well on your way, and would find some grouse. Grouse, however, do have a few other requirements. They will seldom be found in cover less than 10 years old, unless it's full of food, and adjacent to slightly older cover. The type of tree is important too; you'll want to find hardwoods. Hardwoods are species such as Oak, Maple, Dogwood, Poplar, Apple, Thornapple, Alder, and most importantly, Aspen. In short, hardwoods are anything that doesn't resemble a christmas tree. While its not important you remember the species of trees I've listed, you would be wise to remember two of them; Aspen, and Alder. Aspen, identified by it's smooth, almost white bark, and yellow leaves is very important for grouse because of it's ability to re-generate multiple trees from it's root system after being cut, and for the forage its buds provide. Finding Aspen stands often results in good things. Alder can provide good shooting for the uplanders, too. Alder runs are often found in wetter areas which hold woodcock, another wild bird which offers exciting shooting and excellent table fare. Grouse and Woodcock go hand in hand, and should not be over looked. Softwoods, such as Pine, Conifer, Hemlock, and Spruce play a role in a Grouse's life too. These softwoods provide escape and shelter cover from predators and weather. For this reason they are important to grouse, and should register on your radar. Second growth cover interspersed with softwoods, or nearby softwoods is ideally what you'll want to find.

To put it all in a nut shell, ruffed grouse prefer young hardwood lots with a vegetive understory, greater than 20 acres in size, interspersed with stands of softwoods, and usually within 300 feet of open land. This type of cover is really not hard to find. But how does one find it? The first thing you you should know is that another grouse hunter will not tell you where to go. Grouse hunters will discuss habitat type, and hunting tactics, but most, and by most I mean all grouse hunters, pride themselves on having worn out boot leather finding good habitat. That doesn't mean you shouldn't look for advice from them. Many will point you to areas of a state or county with good grouse cover, but it'll be up to you to find the good cover amongst all the other offerings in the area. How do you do that? First, start by familiarizing yourself with whatever grouse cover you are familiar with. Many WMAs have sections of habitat suitable for grouse, which may have been stumbled upon. Many uplanders split their time, sitting in tree stands during the archery season, where a grouse might be happened upon, too. If this has happened to you, remember what that cover looks like, and find other cover that looks the same. After all, this is exactly what all those grouse hunters are doing, but they've just seen more cover. Another easy trick when finding young hardwood cover is to imagine how difficult it'll be to swing a shotgun in it. If I think a cover will be really hard to shoot in, I hunt it. Chances are grouse will be there, and chances are you'll find a way to swing your gun.